A brilliant young Lebanese doctor is helping the country’s cluster bomb survivors receive enhanced treatment, co-creating a revolutionary diagnosis tool that has become invaluable for medical workers caring for blast victims worldwide.

The efforts of Jawad Fares, the son of a neurosurgeon father and an architect-psychologist mother, led him to be named as an ‘Arab Youth Pioneer’ at the World Government Summit in Dubai, while he also features on the 2018 ‘Forbes 30 Under 30’ list.

While such accolades are welcome, Dr. Fares, who’s just 26, is more focused on how he can help society through his work as a senior researcher at the Lebanese University’s Neuroscience Research Center.

“I’m passionate about what I do,” he says. “My purpose is to think of innovative solutions for the health challenges that our community struggles with.”

In 2011, Fares began working with Lebanese wounded by cluster bombs from Israel’s 34-day war against Lebanon in 2006. Finding there was a lack of medical literature on such injuries, he began researching the anatomical, neurological and neuropsychological suffering of civilian victims.

“I hope by shedding light on the effects of these weapons that action will be taken to limit and – if possible – prohibit the use of cluster munitions.”

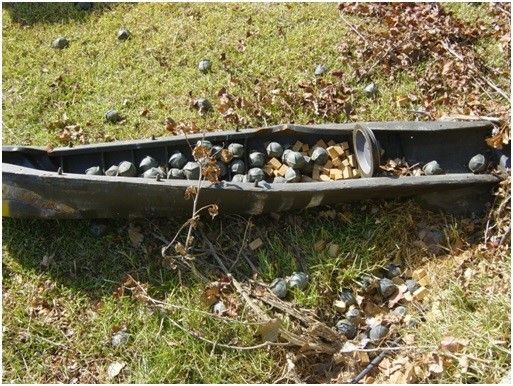

Cluster bombs scatter bomblets across a vast area, but often fail to detonate immediately. During the 2006 conflict, Israeli forces dropped an estimated 4 million bomblets on Lebanon, which a Human Rights Watch investigation found to be both indiscriminate and disproportionate, violating international humanitarian law. Up to 1 million unexploded bomblets littered the urban and rural landscape, causing death and serious injury for years to come.

“For land mines, you can easily just run over them with a special vehicle and they explode, but cluster munitions are released from the air, so they can be left hanging from a tree, or on top of a building where they can be easily triggered by accident,” says Dr Fares, who also holds a bachelor's’ degree in biology and a masters’ degree in neuroscience, studying at both American University of Beirut and Lebanese University.

Lebanon’s doctors treating cluster bomb victims struggled to determine the severity of injuries, which made diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation difficult to deliver. After two years’ toil, Fares and his team developed the ‘Fares Scale of Injuries due to Cluster Munitions’, which grades injuries based on the disability caused. In doing this, doctors can better create an optimum treatment program for survivors.

According to the Fares Scale, Grade I injuries cause functional impairment of less than 25%, Grade II shows 50% disability, Grade III 75%, and Grade IV more than 75% functional impairment. Among Lebanon’s cluster bomb victims, 50% had grade two injuries and 43% had grade one injuries.

Cluster bomb wounds cause mental as well as physical wounds. In 2006, a survey of Lebanese cluster bomb victims found that 98% suffered posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Ten years later, Fares went back and interviewed the same victims, a process that took 14 months to complete. Results showed 43% were still suffering from PTSD, a much higher percentage than has been reported for blast victims and war veterans, while 88% said their injuries had made it difficult to keep a job.

“One of our objectives was to try to help these people,” says Fares, who along with his team put PTSD sufferers in touch with treatment centres, referring the most severe cases for enhanced psychiatric care.

Around 57 square kilometres of Lebanese land was contaminated with cluster bombs from the 2006 conflict, the Lebanese Mine Action Center found, with only 38.5 square kilometres cleared of munitions as of 2013.

“Most people hurt by cluster bombs live in rural areas, so their knowledge of what treatment is available and the existence of care centres is minimal,” said Fares. “There's also a stigma towards mental health. Many victims wouldn’t previously go to a mental health specialist. There's also a lack of rehabilitation centres in Lebanon.”

Today, Fares focuses his research on conflict medicine, neurosurgery, neuroscience and medical education, while he has also co-authored around 40 papers published in international peer-reviewed journals.

He credits his upbringing for his thirst for knowledge and medical discovery.

“Growing up, I would listen to my parents discuss various neural topics and I’d try to make sense of whatever I grasped,” adds Fares. “I remember how my father used to passionately describe neuroscience as the ‘last frontier’, and how it is a universe in 3lbs inside our skulls. ‘Everything we experience is all in that small space’, my father often repeated.”